Across the African savanna, zebras and wildebeests travel together in massive herds often peppered with impalas and gazelles. The larger the herd, the safer its members are from predators like lions, hyenas and African wild dogs.

Scientists have wondered whether dinosaurs similarly engaged in mixed-species herding behavior. Children’s movies like “The Land Before Time” series and “Dinosaur” (2000) often depict motley crews of dinosaurs migrating together, like apatosaurs and triceratops or iguanodons and parasaurolophus (despite often living in different time periods). But evidence that different dinosaur species actually travelled with each other was lacking in the fossil record.

(The Real Wisdom of the Crowds)

Now, paleontologists working in the badlands of Dinosaur Provincial Park in Alberta, Canada, have uncovered fossilized footprints they say provide the first evidence of different species of dinosaurs herding together—though not everyone is convinced. The finding was published Wednesday in PLOS One.

The 76-million-year-old footprints tell the story of a small group of horned dinosaurs, called ceratopsians, that may have formed a Lord of the Rings-esque traveling party with an armored ankylosaurid and, perhaps, a small two-legged theropod. And like Tolkien’s famous fellowship, this band of travelers may have been stalked by fearsome foes: a pair of large carnivorous tyrannosaurs.

RTMP technician working on Skyline tracksite

Photograph by Dr Brian Pickles, University of Reading

Following Footsteps

In the summer of 2024, Brian Pickles, a paleontologist at the University of Reading in England and his colleague Phil Bell were searching for fossils in the park when they came across something strange sticking out of the ground.

“We’d gone out prospecting for bones and weren’t having much luck,” says Pickles. But then Bell, a paleontologist from the University of New England in Australia, came across a raised rim of iron stone. “He started poking around and realized that it was a dinosaur footprint.”

The 48 hours that followed the find were a whirlwind of frantic excavation and profound discoveries that culminated in what he calls “a revolution in dinosaur paleoecology at Dinosaur Provincial Park.”

In a patch of land roughly the size of two parking spaces, the team was able to excavate over a dozen fossilized footprints. Unlike other dinosaur track sites where footprints often overlap, these tracks were evenly spaced and showed no signs of crowding. Based on their size, shape, and direction, the researchers concluded they were likely made by a mixed-species group of at least five dinosaurs walking together. The team also found the fossilized footprints of two large tyrannosaurs that may have been walking side-by-side near the herd.

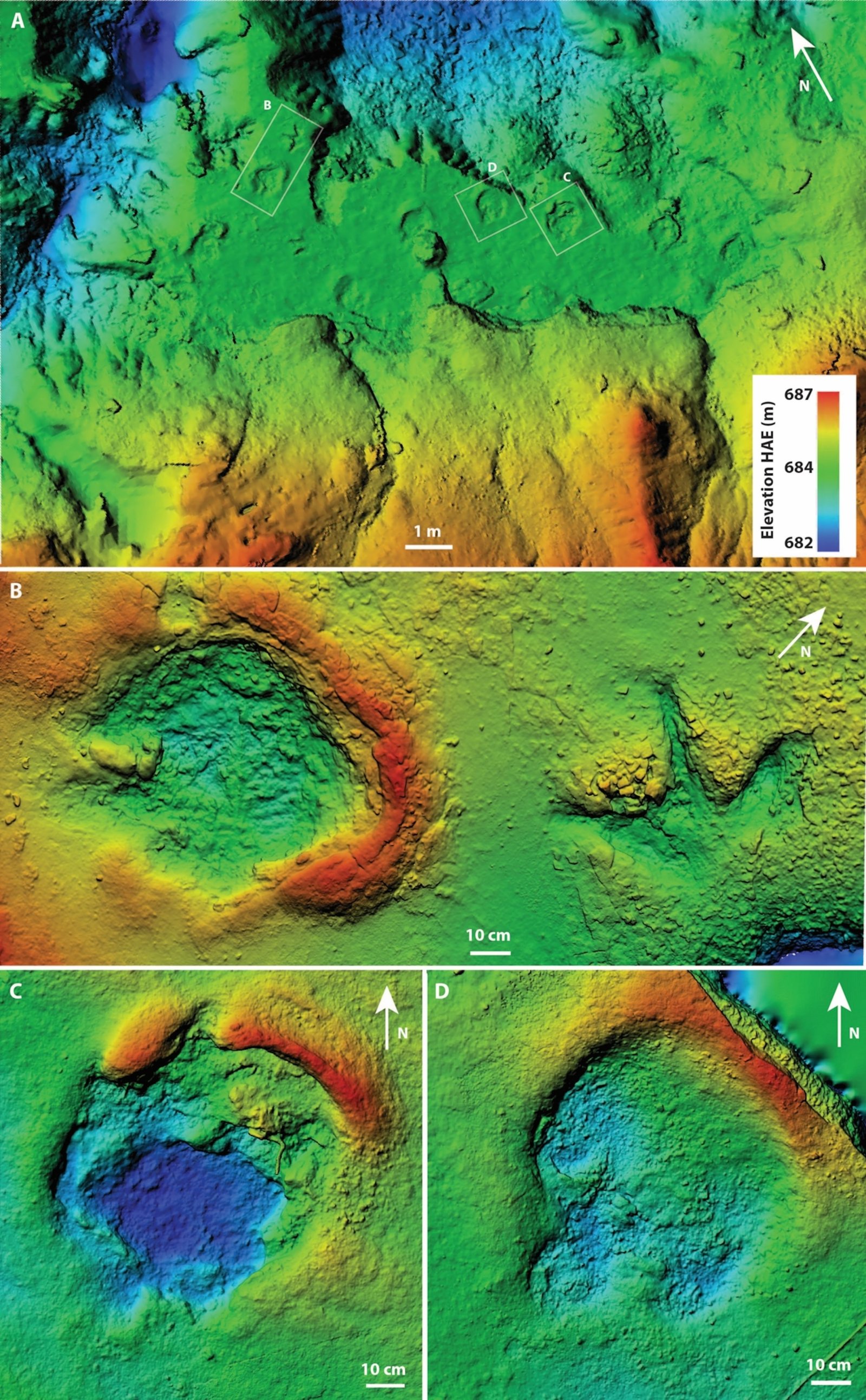

Digital Elevation Model of Skyline tracksite (elevation scale in m) and key tracks (scaled to relative elevation)

Illustration by Dr Brian Pickles, University of Reading

Were these apex predators working together to hunt? And was the herd formed as a way to defend against such predation? In the grasslands of Africa, lions will often follow mixed species herds of herbivores and work together to hunt them. Could these footprints have captured a similar situation unfolding?

“It’s quite evocative to think of this situation as being similar to what we see on the African plains today,” says Pickles. “We don’t know the specific timing. The tyrannosaurs could have been there first.”

‘Weak feet?’

Some researchers not involved in the work questioned the team’s conclusions.

Anthony Romilio, a paleontologist at the University of Queensland in Australia, says that although some dinosaurs likely did form mixed-species herds, he disagrees with how the authors interpreted the footprints.

“As researchers, we’re naturally drawn to the possibilities these fossils offer—but that excitement can sometimes lead to interpretive overreach,” Romilio says. In his view, the ceratopsian and ankylosaurid tracks look similar in shape, and he thinks they are more likely to be poorly preserved footprints of large-bodied hadrosaurs.

“That interpretation may not be as headline-grabbing, but it aligns better with what we know from both fossil footprints and trackways,” he says.

Christian Meyer, a paleontologist from the University of Basel in Switzerland, is also skeptical, and calls the findings “speculative.”

“I find that the preservation of the tracks, including their taxonomic assignment, is on weak feet, as there are no complete trackways preserved that show also the walking pattern,” he says. “Moreover, the interpretation of mixed herding is—given the facts—in my view a bit overstretched.”

Since the excavation that sparked this new study, Pickles and his colleagues say they have found over ten additional dinosaur trackways. With this many trackways, Pickles says, figuring out whether some dinosaurs formed mixed-species herds is just the beginning.

“There’s potentially a lot more going on there than we’ve been able to expose so far,” he says.