This article was produced by National Geographic Traveller (UK).

According to Greek mythology, long ago, Zeus, king of the gods, sent two eagles around the world: one east, one west. The place where they met was the omphalos — the ‘navel’ of the world, a point of connection between divine and mortal planes. Zeus marked it with a sacred stone and a temple was built over it, guarded by his son Apollo. The place was called ‘Delphi’ — and it was here that a priestess known as the Oracle was said to deliver prophecies from the gods.

“People often think the Oracle foretold the future,” explains archaeological guide Penny Kolomvotsou, when I meet her outside the gates of the Athena Pronaia, a sanctuary where pilgrims would once have entered Delphi’s holy complex. Penny — her eyes shielded under a sun visor, hair pulled back into a tight ponytail — is a Delphi regular; the site attendants greet her with a wave and a smile. “In fact, her prophecies were deliberately cryptic, open to interpretation. Really, Delphi was a place of dialogue. We could use more of that nowadays, I think.”

In the ancient world, she explains, Delphi was where Greek’s fractious city states settled disputes without resorting to conflict. Ambassadors came here to resolve their differences peacefully, while ordinary pilgrims — at least those who could afford it — sought spiritual guidance or the blessing of the gods for important life decisions. Most of them would have arrived on foot, trekking up to the temple eyrie from the surrounding villages of the Amfissa Valley or nearby Mount Parnassos.

Delphi was where Greek’s fractious city states settled disputes without resorting to conflict.

Photograph by Oliver Berry

At the heart of the complex was the Oracle — otherwise known as the high priestess Pythia — who was believed to be able to commune directly with the gods through a form of divine possession known as enthusiasmos. Mentions of the Oracle date back right to the temple’s earliest origins in the sixth century BCE, but much about her role remains shrouded in mystery.

It’s autumn but still blazingly hot, breezeless and searingly blue. Despite the heat, Delphi’s packed. Coaches chug up the mountain road, grinding gears as their drivers hunt for parking spots. Delphi would have been no stranger to crowds, Penny says, especially during the Pythian Games. Held every four years as a display of athleticism and physical prowess, they were the most important games after the Olympics. We walk past the abandoned stadium, and I imagine crowds seated on the stone rows, snacking on olives and figs as they cheered on their favourite competitors.

Held every four years as a display of athleticism and physical prowess, the Pythian Games were the most important games after the Olympics.

Photograph by Oliver Berry

In ancient Greece, temples were built high up to be near the gods. Delphi teeters on the slopes of Mount Parnassus, guarded by twin cliffs called the Phaidriades, or the Shining Rocks, a poetic reference to the limestone’s glare. We trudge up a path worn smooth by thousands of feet — the ascent was a test of pilgrims’ stamina as much as their piety. Step by step, Delphi’s tumbledown landscape emerges: stone blocks, crumbling altars, empty plinths and shattered columns.

“Archaeology has revealed so much,” explains Penny. “But there are still many mysteries.” The Oracle’s prophecies were often more like riddles than rulings; the gnomic maxim ‘know thyself’, carved at the entrance to the complex, is perhaps the best example of all. Equally mysterious is how the Oracle physically received and dispensed her prophecies. Some archaeologists believe she entered her trance through prayer or meditation; others say her revelations came after inhaling narcotic fumes, perhaps even gases emanating from geological faults under the mountain. Like so much about Delphi, it’s a conundrum that could only be solved with the help of a time machine.

In ancient Greece, temples were built high up to be near the gods. Delphi teeters on the slopes of Mount Parnassus, guarded by twin cliffs called the Phaidriades.

Photograph by Oliver Berry

Lost in time

The next day, I set out along the Archaio Monopati, the millennia-old footpath pilgrims would have followed up to the temple from Delphi’s ancient port, Kirra. En route, they’d have crossed the grey-green ocean of the Amfissa Valley, one of Greece’s oldest olive groves. Cultivated since before the time of Christ, it’s home to more than a million trees. Today, I’m alone on the path, save for an ill-tempered goat and an olive-farmer tending his trees.

Joining me is Hilda Giannopolou, a hiking guide and ski instructor from the mountain town of Livadi. “I love Delphi because you can feel the history,” she says. “We’re walking in a landscape that hasn’t changed in 2,000 years. You don’t have to believe in gods to feel its power.”

The grey-green ocean of the Amfissa Valley, one of Greece’s oldest olive groves. Cultivated since before the time of Christ, it’s home to more than a million trees.

Photograph by Oliver Berry (Top) (Left) and Photograph by Oliver Berry (Bottom) (Right)

We hike up to a ridge, and sit beside a whitewashed chapel overlooking the plain, with Delphi’s ruins glinting on the mountainside above us. Under the shadow of the bell tower, we picnic on bread, tomatoes and cheese, sprinkled with sage, thyme and lavender gathered from the valley. It’s exactly the sort of lunch pilgrims might have munched on 2,000 years ago.

The most remarkable thing about Delphi is the fact it still exists at all. After the fall of two empires — first Greek, then Roman — Delphi and its Oracle was forgotten, and the location of Apollo’s holy sanctuary was lost. It was rediscovered by French archaeologists in the 19th century, buried underneath the village of Kastri, whose foundations were fashioned from its ruins. The villagers were relocated to a nearby site — present-day Delphi — and the painstaking, decades-long excavation of the temple began. Sadly, by then, many of its secrets had already been lost in time.

After the fall of two empires, Delphi and its Oracle was forgotten. It was rediscovered by French archaeologists in the 19th century, buried underneath the village of Kastri. The villagers were relocated to a nearby site — present-day Delphi.

Photograph by Oliver Berry

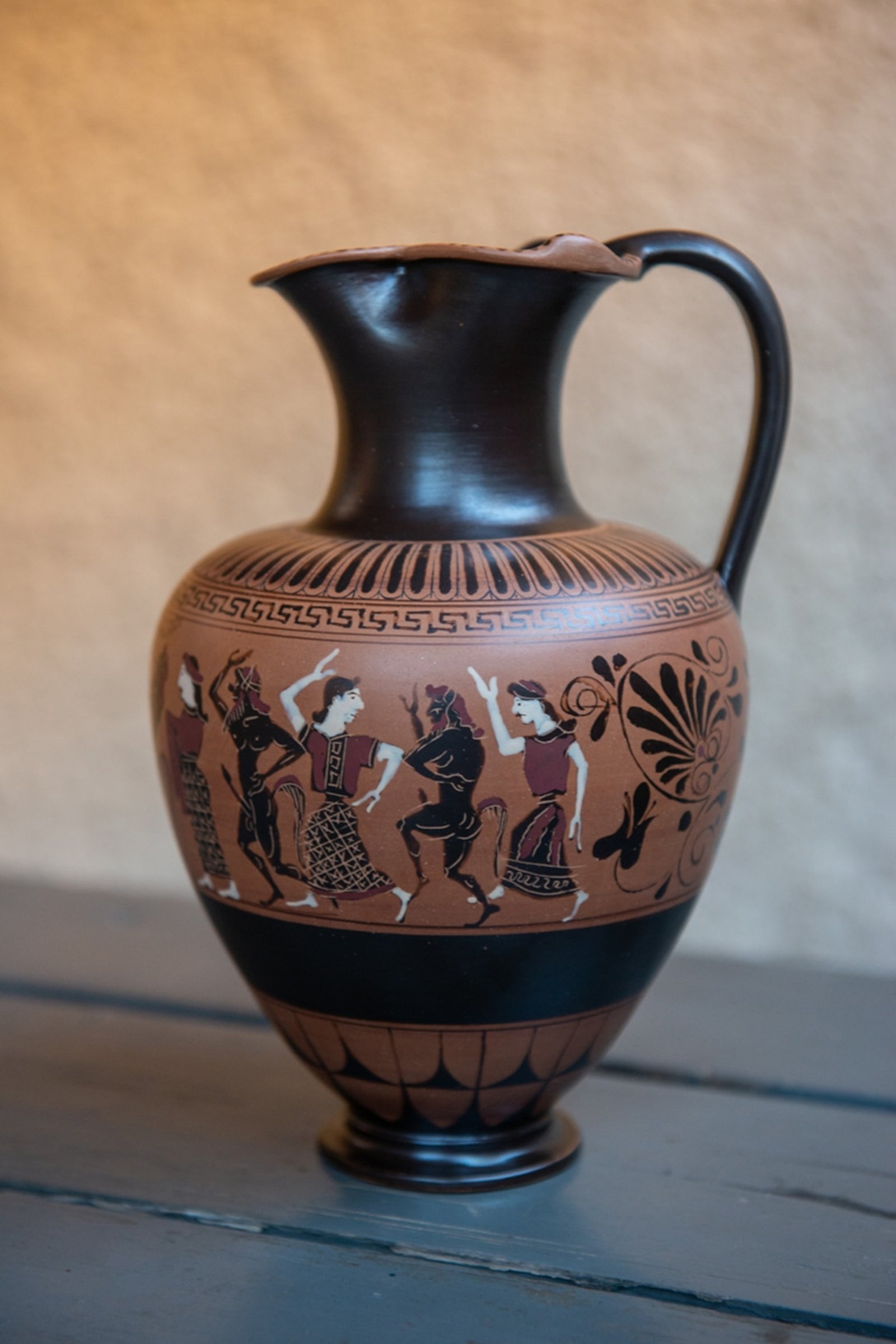

One man doing his best to rediscover them is Aristotelis Zisimou, who’s devoted his life to relearning the art of Delphic pottery. I meet him at his studio in Delphi, on a quiet backstreet shaded by bougainvillea and jasmine trees. Here he runs pottery classes and makes his pieces — hand-mixing his own clay, etching designs and, finally, firing them using a special technique to create the orange-and-black finish characteristic of classical Greek pottery. It’s a complicated process requiring precisely the right combination of heat, materials and carbonation. Some techniques Aristotelis learned from other like-minded potters, but much he gleaned through trial and error, just as Delphi’s own potters likely did nearly 1,500 years ago.

Aristotelis shows me around his workshop, where classically shaped amphoras, dishes, plates and bowls sit alongside more experimental modern designs. Many depict scenes from myth and legend and are often startlingly explicit — a reminder of the close link between sex and the sacred in the ancient world. “My work connects me to the artists of the past,” he says, gazing at me over his glasses as he puffs on a battered cigarette, etching a figure into the clay with a fine needle pick. “Sometimes, I can almost feel them guiding my hand.”

Aristotelis Zisimou has devoted his life to relearning the art of Delphic pottery.

Photograph by Oliver Berry

Zisimou hand-mixes his own clay, etches designs and, finally, fires them using a special technique to create the orange-and-black finish characteristic of classical Greek pottery.

Photograph by Oliver Berry

The following morning, I follow a tip from Aristotelis and set out to find the Corycian Cave, Delphi’s oracular antecedent. Long before the Oracle existed, Aristotelis had told me, worshippers of Gaia, the mother goddess, held sacred rites in the mountains. The Corycian Cave is thought to have been used since Neolithic times. It appears in many myths — a place of Dionysian rituals, dedicated to Corycian nature nymphs and to Pan, god of the wild, it’s also where Zeus was believed to have been imprisoned by the giant Typhon. It’s almost certainly the oldest Delphi shrine of all.

Just after sunrise, I drive up from Delphi onto a plateau under Mount Parnassus, following a rocky road up through a pine forest. Here, at the end of a short, stony trail through the trees, I find a cleft in the mountainside, black as night. Warily, I inch inside, and find myself inside a great, high-ceilinged cavern, festooned with stalagmites and stalactites. It’s so deep the other side is lost in the gloom. On the floor, someone has built a labyrinth out of stones. There are embers from a fire, offerings of wine, water, bracelets, money. Those pilgrims who couldn’t afford to consult the Oracle — or who perhaps preferred the advice of even older gods — are said to have come to the Corycian Cave instead to ask for divine guidance. More than two millennia later, it seems, people are still doing the same.

I send my own prayer echoing into the darkness and wait for the gods to answer.

Published in the April 2025 issue of National Geographic Traveller (UK).

To subscribe to National Geographic Traveller (UK) magazine click here. (Available in select countries only).