The dispersal of archaic hominins beyond mainland Southeast Asia (Sunda) represents the earliest evidence for humans crossing ocean barriers to reach isolated landmasses. Previously, the oldest indication of hominins in Wallacea, the oceanic island zone east of Sunda, comprised flaked stone artifacts deposited at least 1.02 million years ago at the site of Wolo Sege on the island of Flores. On Sulawesi, the largest Wallacean island, previous excavations revealed stone artifacts with a minimum age of 194,000 years at the open site of Talepu. Now, archaeologists from Griffith University show that stone artifacts also occur at the nearby site of Calio in fossiliferous layers dated to at least 1.04 million years and possibly up to 1.48 million years. This discovery suggests that Sulawesi was populated by hominins at around the same time as Flores, if not earlier.

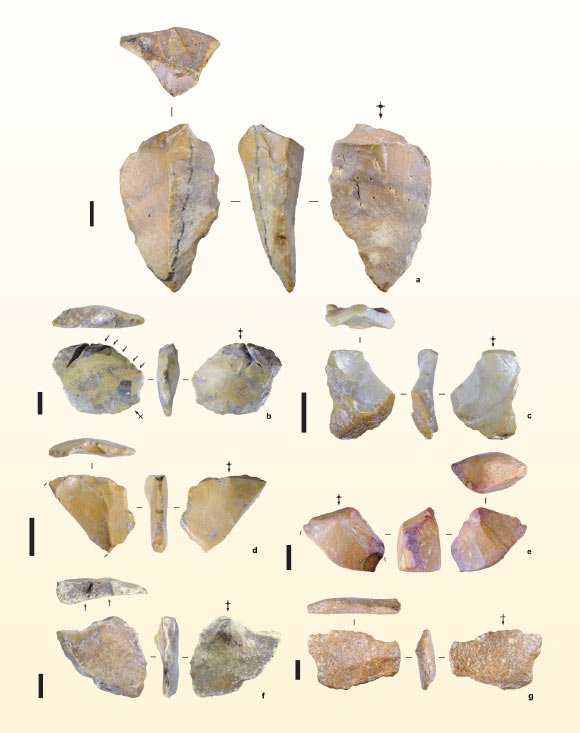

Griffith University’s Professor Adam Brumm and his colleagues excavated a total of seven stone artifacts from the sedimentary layers of the Calio site.

In the Early Pleistocene, this would have been the site of hominin tool-making and other activities such as hunting, in the vicinity of a river channel.

The Calio artifacts consist of small, sharp-edged fragments of stones (flakes) that the early human tool-makers struck from larger pebbles that had most likely been obtained from nearby riverbeds.

“This discovery adds to our understanding of the movement of extinct humans across the Wallace Line, a transitional zone beyond which unique and often quite peculiar animal species evolved in isolation,” Professor Brumm said.

The archaeologists used paleomagnetic dating of the sandstone itself and direct-dating of an excavated pig fossil, to confirm an age of at least 1.04 million years for the Calio artifacts.

Previously, they had revealed evidence for hominin occupation in Wallacea from at least 1.02 million years ago, based on the presence of stone tools at Wolo Sege on the island of Flores, and by around 194,000 years ago at Talepu on Sulawesi.

The island of Luzon in the Philippines, to the north of Wallacea, had also yielded evidence of hominins from around 700,000 years ago.

“It’s a significant piece of the puzzle, but the Calio site has yet to yield any hominin fossils,” Professor Brumm said.

“So while we now know there were tool-makers on Sulawesi a million years ago, their identity remains a mystery.”

Stone artifacts from the site of Calio, Sulawesi, Indonesia. Image credit: Hakim et al., doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09348-6.

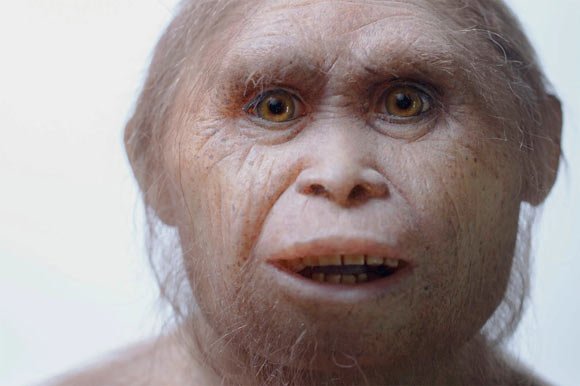

The original discovery of Homo floresiensis and subsequent 700,000-year-old fossils of a similar small-bodied hominin on Flores suggested that it could have been Homo erectus that breached the formidable marine barrier between mainland Southeast Asia to inhabit this small Wallacean island, and, over hundreds of thousands of years, underwent island dwarfism.

“The find on Sulawesi has led us to wonder what might have happened to Homo erectus on an island more than 12 times the size of Flores?” Professor Brumm said.

“Sulawesi is a wild card — it’s like a mini-continent in itself.”

“If hominins were cut off on this huge and ecologically rich island for a million years, would they have undergone the same evolutionary changes as the Flores hobbits?”

“Or would something totally different have happened?”

The study was published yesterday in the journal Nature.

_____

B. Hakim et al. Hominins on Sulawesi during the Early Pleistocene. Nature, published online August 7, 2025; doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09348-6