Italian genre specialist Stefano Sollima — best known for the gritty TV hit “Gomorrah” and movies such as “Sicario: Day of the Soldado” and “Without Remorse” — spent more than a year researching the still unsolved case at the heart of his new Netflix series “The Monster of Florence,” premiering on Thursday at Venice Film Festival.

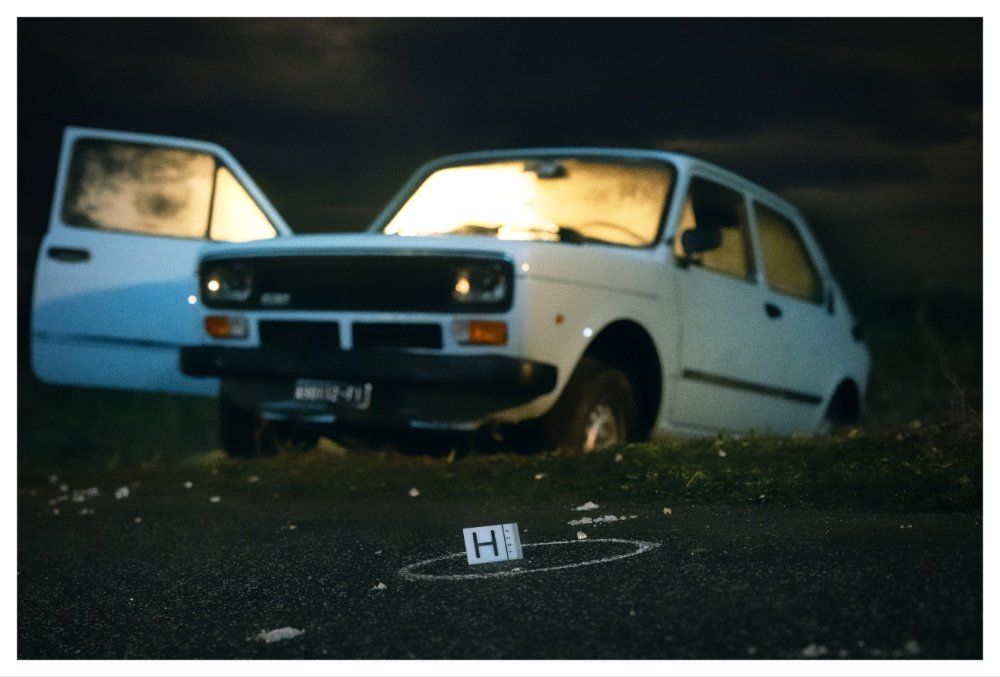

The show’s title is the moniker given to the alleged serial killer, who committed eight double murders over the course of 17 years from the late 1960s to the mid-’80s, preying on couples parked in cars in secluded places around Florence. “The Monster” always used the same weapon, a 22 caliber Beretta.

The four-episode limited series, which drops on Netflix Oct. 22, was shot largely on location in Florence and its surroundings. It reunites Sollima with writer Leonardo Fasoli and ace Italian cinematographer Paolo Carnera, both of whom Sollima worked with on “Gomorrah.”

Popular on Variety

Sollima spoke to Variety in Venice about how he tackled this gruesome material and why he chose to follow several investigative strands in the cold case, starting with the one known as the “Sardinian lead,” spawned by a Sardinian couple living in Tuscany with infidelity issues.

What drew you to this project?

The story actually chose me. Out of all the possible projects I had, it’s the one that struck me the most. I started reading books about the case and, while being very authoritative, they all had a flaw: each one had its own thesis and slightly bended reality to support their theory. So I said, “Oh my God, it’s a very complex story! But it must be told in a way that’s not banal.” It poses the problem of, how do you tell the story of an investigation that spans over a long period of time and how do you tell this story without embracing a theory?

That’s when we came up with the idea of using the hunt for the Monster of Florence as an overall backdrop, but with a different suspect in each episode. This allowed us to avoid having to pick an investigative theory. By doing so, we were able to embrace all the theories and slightly broaden the story, which isn’t just a crime piece. Describing the suspects individually allowed us to investigate monstrosity in a broader sense — not just the alleged Monster of Florence, but the monstrosity that some of these characters displayed in their intimate relationships, family relationships and friendships. So suddenly, we realized that the story was becoming much broader and centered not so much on the hunt for the Monster of Florence but rather an investigation of man and how he is a bearer of evil.

One thing that struck me is that the investigating magistrate, who is a woman, points out that the violence is specifically directed at women. That element seems to be part of the broader narrative, am I right?

Absolutely. It was one of the elements that struck us, because if you reread all the documents relating to the very first murder you notice the prejudice that existed on the part of the investigators. They found a dead woman with her lover, so obviously what did they do? They went looking for another lover, which is a form of prejudice that becomes their obsession. And that is how they begin to lose other pieces that perhaps could have been crucial to solving the case. Also, the way the bodies were found was emblematic. We did some truly distressing research, especially because we had to see material that perhaps would have been better left unseen. It suggested that this was a form of violence obviously very much directed at women.

Compared with “Gomorrah,” the tone in “Monster” is more restrained. It’s a meticulously researched crime drama and a period piece, of course. How did you set this tone?

“Gomorrah” was inspired by true stories, but we had more creative freedom because the characters’ names weren’t real. Here, we made a completely opposite choice, because we chose to use the protagonists’ real names. The moment you make and implement that choice, you no longer have room for dramatization or creative intervention. Creative intervention boils down to simply deciding how to organize the material narratively. So paradoxically, it’s as if you were forced by your own approach to take a step back. In terms of the physical representation of the violence of the murders, I’ve seen photos, some taken by forensic scientists, and it really hurt me to look at them. Obviously you have to face the problem of how to stage the murders, right? Do you turn them into spectacle? You’re writing a genre story, so that could be okay, right? Nope. Absolutely not — also, out of respect for the real victims.

So, what do you do? You have to find a compromise, in which you tell what’s strictly necessary to understand the atmosphere of the story. Perhaps that’s part of the restraint you feel. Then there is the violence depicted in the psychological exploration of the characters, but that is also very respectful of the original story. There was no need to dwell on details, using gore and splatter.

One common element “Monster” has with “Gomorrah” is they are shot by the same cinematographer, Paolo Carnera. What type of notes did you give him?

We shaped the visuals starting from some basic facts. One is that our story would take place largely at night, which was obviously a limitation in production terms, especially for a streamer audience. So we tried to figure out how to maintain a natural photographic approach, but without making it completely black, as it would have been in reality. The Monster struck on moonless nights precisely because he took advantage of the virtually total darkness. So we started from the darkness, and we found ourselves figuring out how to make the scenes visible with the style and ability that Paolo, whom I’ve known for ages, has. I think he’s one of the masters of nighttime cinematography, and world class. We are a thoroughly tested, well-oiled team, so we don’t even need to talk that much. It’s quite instinctive.

“The Monster of Florence”

Courtesy Netflix