Get the Popular Science daily newsletter💡

Breakthroughs, discoveries, and DIY tips sent every weekday.

A delicate, antique Buddhist scroll crafted by Mongolian nomads has finally been unfurled after spending decades in museum storage. But the team at Germany’s Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin (HZB) research institute didn’t risk any damage by physically unrolling it—they peered inside using a combination of 3D X-ray tomography and AI assistance. The process, as well as what they found written inside, are detailed in a study published in the Journal of Cultural Heritage.

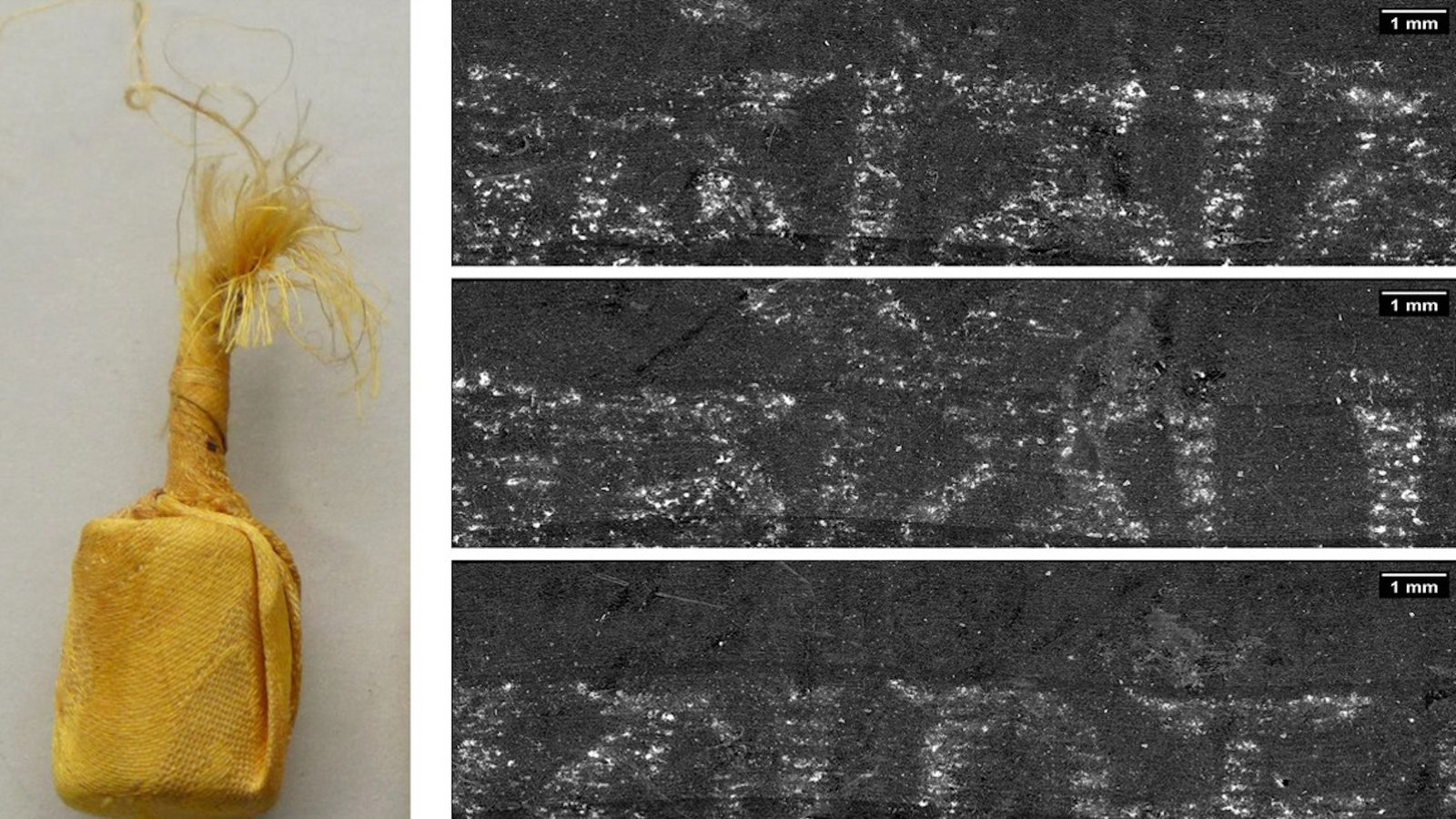

For centuries, the nomadic peoples of Mongolia owned only what they and their pack animals could carry. For Buddhist families, this often included a gungervaa, a portable shrine containing artwork, decorative objects, and other spiritual keepsakes. Some of the most notable items were dharanis—tiny, tightly rolled scrolls featuring common prayers wrapped in silk that generally measured no more than 1.9 by 0.7 by 0.7 inches. The tradition was almost entirely wiped out during the Soviet-backed Mongolian Revolution of 1921, with many of the artifacts destroyed in the process. One shine survived the era, and although its origins are unclear, the relic ultimately arrived at Germany’s Ethnological Museum of the National Museums in 1932.

Much to conservationists’ dismay, the shrine is no longer arranged as it was when it entered the archive. After being disassembled for storage, some items were damaged during World War II, and four gilded bronzes and a small painting have disappeared entirely. Nonetheless, over 20 objects–including fabric flowers and statues–are still preserved at the Ethnological Museum, along with three small dharanis in yellow silk bags.

Scanning at sub-volume levels

Until only a few years ago, accessing the scrolls required archeologists to extract and unroll the delicate papers without compromising the materials—an extremely risky venture. Rather than risk ruining the scrolls, museum researchers requested to borrow a 3D X-ray topographical scanner from the country’s Federal Institute for Materials Research and Testing (BAM).

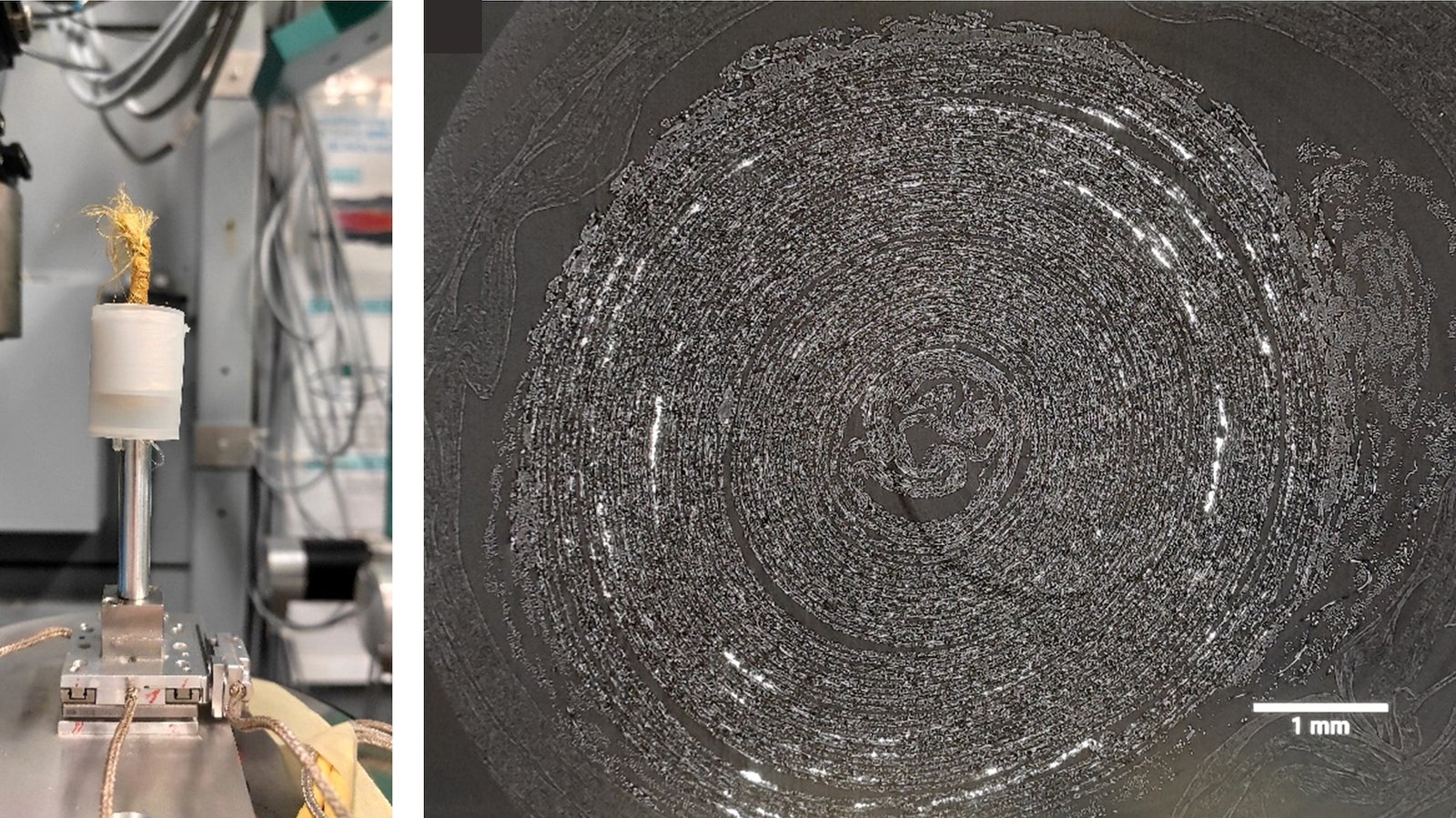

The scanner relies on synchrotron tomography, an advanced imaging method that uses hard X-rays to compile 3D representations of an object, beginning at the microscopic level. While frequently used in engineering and material sciences (such as advanced battery research), preservationists are increasingly utilizing the technique for cultural and archeological work.

Operating the scanner on the dharanis presented a hurdle, however. The equipment’s imaging beamlines have a limited field-of-view, requiring the handlers to image the objects as a series of “sub-volumes” at multiple height positions. According to the study, each sub-volume required a stack of 2,570 projects taken over 180 degrees. Once finished, these scans could be combined to form a single, detailed image.

Each scroll contained over 31.5-inch strips of parchment wound tightly about 50 times before being stored in their silk pouches. The discoveries didn’t end there—by enlisting AI analysis programs, researchers could examine the scrolls’ remaining ink traces. Although Chinese ink frequently consists of a mix of animal glue and soot, experts were surprised to learn that the dharanis’ ink contained metal particles.

Another unexpected discovery came from a portion of discernible writing inside a scroll. At one point, Tibetan characters spell out the Tibetan Buddhist mantra for universal compassion, “Om mani padme hum” (literally, “praise to the jewel in the lotus”), but not in the native language. Instead, the author used Sanskrit grammar to pen their prayer.

The study’s authors cautioned that while extremely helpful, X-ray tomography remains “labor-intensive and cannot yet be used as a standard [method].”

“Nevertheless, it offers unique opportunities to unroll or unfold scrolls where promising texts are expected,” they wrote.

The team hopes that with additional advancements, X-ray tomography will increasingly offer opportunities for collaborative, interdisciplinary projects that delve into currently inaccessible artifacts. According to Ethnological Museum preservationist and study co-author Birgit Kantzenbach, it’s a vital part of conservation work.

“An object always means only what people see in it; that’s what’s important,” she said in a statement.

More deals, reviews, and buying guides

The PopSci team has tested hundreds of products and spent thousands of hours trying to find the best gear and gadgets you can buy.